Bridging Classrooms and Voices: A CHL Curriculum Rooted in Social Justice

Guest post by Lini Ge Polin of University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and Bonnie Wang of Durham Academy, recipients of an honorable mention for the 2025 MAFLT LCTL Innovation Awards.

When we first came together to rethink how we teach Chinese as a Heritage Language (CHL), we knew we wanted more than just a language curriculum. We wanted to create something that honored our students’ identities, challenged them to think critically, and made space for their voices.

Over the past few years, we’ve designed and implemented a thematic unit on social justice for CHL learners at two very different institutions: a private high school and a public university. Though our students varied in age and proficiency, they shared similar backgrounds and questions about identity, culture, and belonging. This became our starting point.

Why We Did This

As Li and Duff (2018) noted, heritage language programs often fall short in adapting to the specific needs and goals of CHL learners. Too often, curriculum and assessments are designed with non-heritage learners in mind. We saw this gap firsthand and wanted to create something better – something responsive, rigorous, and relevant. We built our curriculum around the experiences of Asian Americans, using language learning as a means to explore immigration histories, media representation, and anti-Asian discrimination. Grounded in Mezirow’s (2003) transformative learning theory, we aimed to move beyond vocabulary and grammar drills toward reflective, critical engagement in Chinese.

A Shared Journey

One of the most rewarding aspects of this project has been the collaboration between institutions, instructors, and most importantly, students. We structured our units around service-learning and project-based learning, selecting authentic materials (e.g. news articles, interviews, and YouTube videos) and modifying them to suit our students’ proficiency levels. High school students (Intermediate Low–Mid) and college students (Intermediate Mid–High) engaged with similar content, but through differentiated activities. For example, while college students wrote reflection papers, high schoolers created “Lunchbox Projects” where they told personal stories through food, language, and cultural symbolism.

We used tools such as Padlet, Jamboard, Flipgrid, and Google Slides to support asynchronous and synchronous engagement. Padlet became our virtual gallery for student reflections on family immigration history. Flipgrid allowed students to practice oral storytelling. These tools helped bridge the physical and cognitive distance between our classrooms, and enabled students to express themselves in multiple ways.

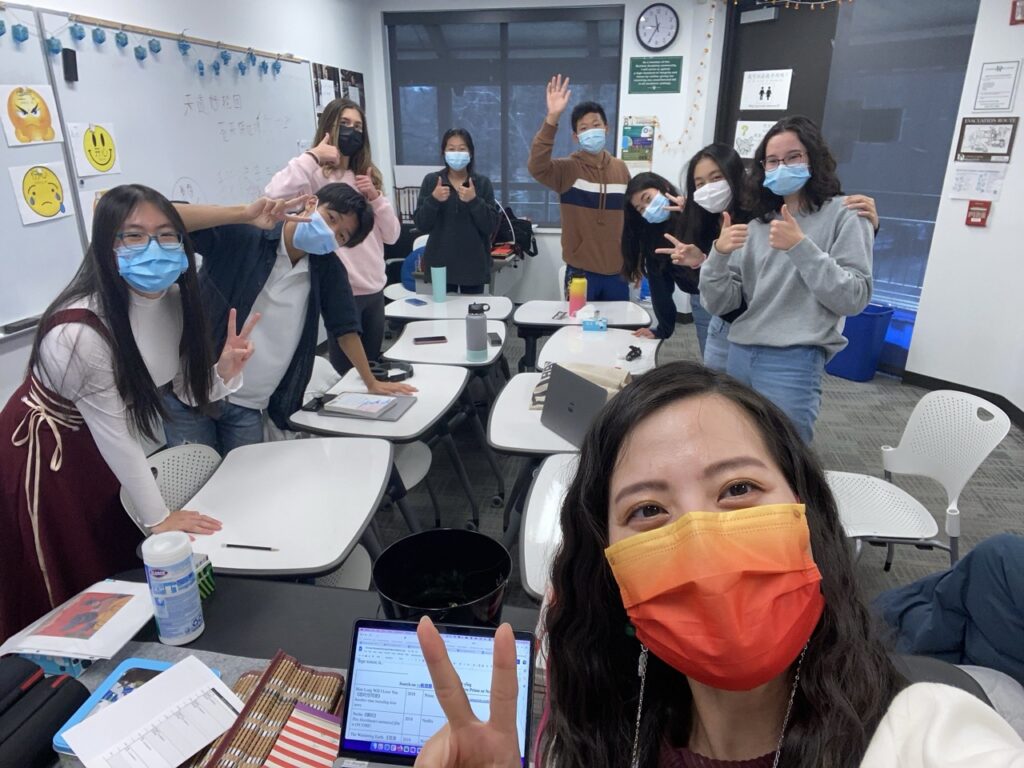

The highlight of the project was a culminating field trip where the high school class visited the university campus. In small groups, college students introduced key vocabulary and concepts, then led collaborative discussions on anti-discrimination strategies. The session ended with the high schoolers presenting their lunchbox projects, creating a full-circle moment of shared learning and expression.

What We Saw

The impact was immediate and lasting.

Students became more confident in their language use and more open in their discussions. They connected what they were learning in class to what they were seeing in the world, especially during times of rising anti-Asian sentiment. They asked bigger questions, made deeper connections, and began seeing Chinese not just as a language, but as a tool for advocacy and storytelling.

Our pre- and post-unit surveys showed increased engagement and critical thinking across both student groups. But beyond the data, it was the conversation that stayed with us – students discussing their grandparents’ immigration stories, analyzing media portrayals of Asian Americans, or brainstorming ways to address bias in their schools and communities.

As instructors, this experience transformed our own teaching practices. We became more intentional in how we design assessments, more flexible in how we use technology, and more collaborative in how we connect across institutions. This project reminded us that powerful learning happens when students feel seen, and when we listen.

Looking Forward

We are incredibly honored by this award, but more importantly, we’re excited about what’s next. We’re continuing to refine this unit and share it with others. We believe the model collaborative, accessible, and identity-affirming can be adapted not just for CHL contexts but for other Less Commonly Taught Languages (LCTLs) and heritage programs.

If you’re curious about implementing something similar, our advice is simple: start with your students. Learn their stories. Build from what matters to them. And don’t be afraid to experiment with tools, with collaboration, and with what language education can be. Let’s keep pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in heritage language education together!

References

Li, D., & Duff, P. (2018). Learning Chinese as a heritage language in postsecondary contexts. In C. Ke (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of Chinese second language acquisition (pp. 318-335). New York: Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344603252172