Using Virtual Reality to Promote Cultural Learning in the Classroom

Guest post by Juliano Saccomani, Assistant Instructional Professor of Portuguese at the University of Chicago and winner of the 2025 MAFLT LCTL Innovation Awards.

Virtual Reality is ever-more present in our daily lives: from creating entire virtual worlds into which we can delve and explore, to augmenting our reality and seeing Pikachu frolic around our apartments, the possibilities make this a technology we cannot ignore. And with the advances in headsets and gears that facilitate our immersion into different worlds, it would be a shame to not use this in education. In my project, I use virtual reality headsets to help my students to see and experience other cultures in the target language (Portuguese in my case). The entire process involves a few other elements which I will explain below, but the ultimate goal is to give them the opportunity to see what they want, and to focus on whatever cultural aspects catch their attention during the immersive experience. By doing so, I’m looking into providing students with materials that they will then associate with their own personal experiences to better analyze and understand other cultures.

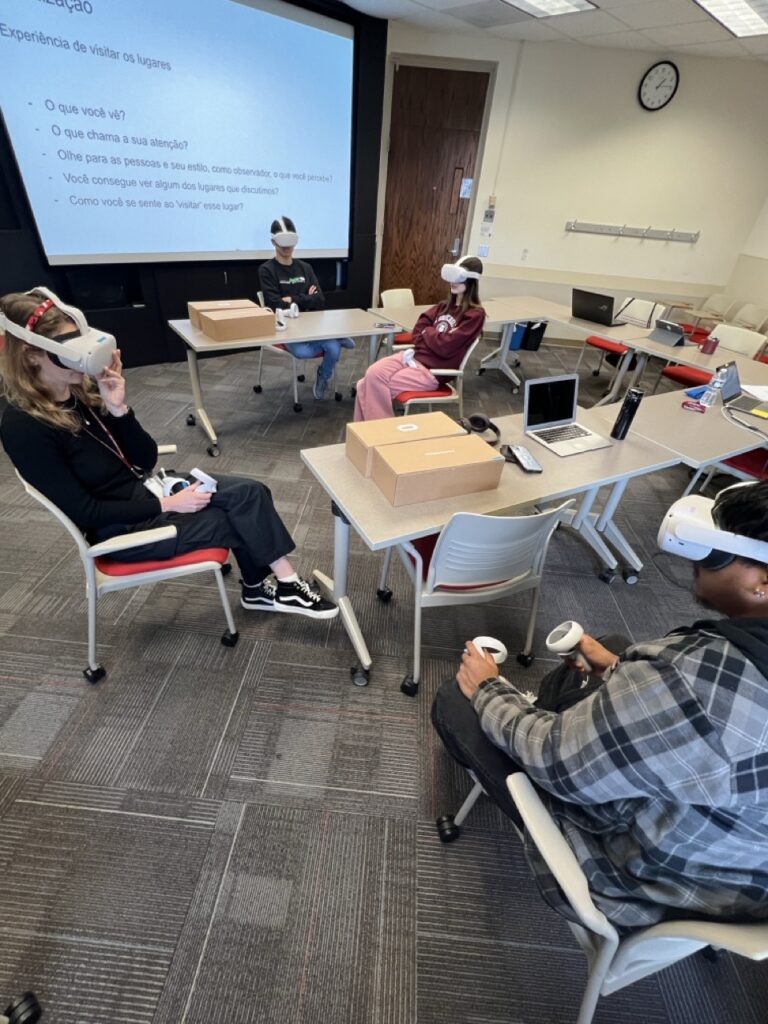

By using headsets with immersive capabilities, I offer students the opportunity of finding themselves in places of the Portuguese-speaking world. For example: I have activities in which students take a motorcycle ride through the streets of Luanda, in Angola; or they could also watch daily-life enveil itself before their eyes as they sit in a historic site in Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil; or they could even have a walk by the Jeronimos Monastery in Lisbon, Portugal.

These all seem like nice sights for one to see, and, ordinarily, they are: those videos are full of great sights, and they are somewhat calming as you just observe daily life go by, as a good flâneur. But as language and culture instructors, we always try to offer the best experience to our students: if you prepare students prior to class, they may be able to take more than just, quite literally, meets the eyes.

The methodology has students go over preparatory material that will present students with social, historic, geographic, or economic intricacies of the contexts they will ‘explore’ in class. Then, students have either a guided discussion, or a prompt for a written response to the material they studied, which will be used as their basis when they are immersed in those virtual realities. This way, when we get to ‘visit’ those locations, students will have a bit more knowledge of what they can see. Going back to my previous examples in the Portuguese-speaking world: they will know that in Luanda, mostly the tourist streets by the seashore are the ones that are highly developed; they will know that the square in Rio de Janeiro in which they are sitting was once where the Portuguese Crown used to live; and they will know that the Jeronimos Monastery, even if it is a religious place, is full of nautical theme – since it was built in order to celebrate the Portuguese people being the first ones to circumnavigate the globe.

But there is more to it, because, once immersed, students are free to catch up on those aspects – or not! They have the agency to observe whatever they want, much like bringing a group to a field trip, you can call their attention to a historical monument, but they can choose to look at the pigeons covering the square around it. They can extrapolate the historical meanings to seeing the people who go around those places, their daily habits, how they interact with each other and with the places we visit. Students can see the daily lives in those locations brimming with significance, but that, in a student’s perception, could be overshadowed by a hot-dog vendor and his interaction with their client, or by the children playing soccer in the middle of the street.

This is the beauty of this project, students are as much a part of what they learn than the instructor is. The instructor leads the way with the preparatory materials, the guiding preliminary work, and with preparing the material to be visualized. After that point, it’s the students’ responsibility to make their own connections and draw significance from the immersion experience. And in order to have a proper debrief moment, it’s up to the instructor if they want a quick 5-minute conversation, or if they want a student to write a reflection piece on what they saw and understood. I have worked with both, to great amazement after I saw how students went beyond my wildest expectations.

This activity can be scaled up or down in terms of language use or proper goals for each class. I also understand that the cost of acquiring headsets for full classes of students could be an impediment for people to start working with this technology. I have been exploring multiple products – namely the Quest headsets but also headsets in which students place their phones – each with different results and usability. The Quest headsets showed better results with videos, but the phone-in headsets were better for working with pictures and more elementary language-exchange activities. The second example here could be a good fit for programs that want to start and to get the ball rolling to get their VR programs started.

We have also received great feedback from different parties involved in the process: such as from students by mentioning they perceive the relevance of using VR for cultural learning; from peers as they see how implementing VR activities could increase enrollment in LCTLs and also open up the borders of the classroom; and from the administration by mentioning how such projects help to advance and innovate teaching standards and practices on campus. Luckily I was able to have a great support system, and the financial means to start working with this, but I would be happy to work with anyone who is reading this and have them think of possible ways of working around what they see as blocks to them starting their own project. The ultimate goal is to make virtual reality become a reality in classrooms all over the place.

I would like to give special thanks to Claudia Quevedo-Webb, Ana Lima, Nené Lozada, and Nicolas Portugal, Ana Marcelino, Tyler McBride, Francisco Barradas, and The University of Chicago Language Center, all of whom have been fundamental in the creation and continuation of this project.